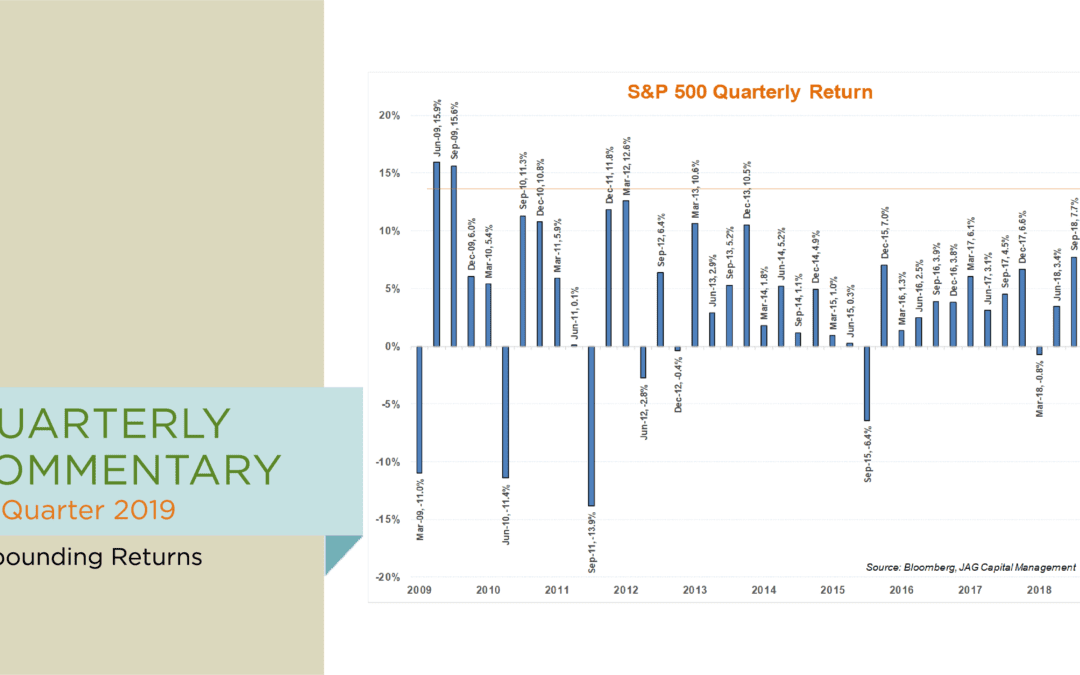

Storm clouds gave way to sunshine for investors during the first quarter of 2019, resulting in very strong returns for risk assets. The S&P 500 Index posted a 13.65% return in the three months ending 3/31/19, representing its best quarterly gain since late 2009 and its best first quarter since 1998. As if investors needed to be reminded, the last seven months have provided yet another example of the fickle nature of financial markets. In that short span of time, the S&P 500 has gone from setting all-time highs last September, to a roughly 20% decline that bottomed with climactic selling on Christmas Eve, only to rally furiously back to within 3% of the record high. Besides providing an excellent example of the futility of market-timing, recent experience buttresses the point that short-term volatility is the price equity investors must pay to capture the premium long-term return potential of stocks. Decades of evidence has shown that investors who overreact to the inherently schizophrenic nature of stock prices tend to earn substantially lower returns than they would have otherwise (more on this in a moment).

Federal Reserve policy has been in the spotlight in recent months. Remember that after years of maintaining the Fed Funds rate at zero, the Fed began raising short-term rates in December 2015. Including the most recent .25% increase in December 2018, the Fed has hiked rates nine times over the past three years. Furthermore, as late as early October of last year, the Fed was indicating that future rate hikes were likely to occur into 2020. But as is always the case, investors and markets get to “vote” on central bank policies. The Fed heavily influences short-term bond yields via their power to set the Fed Funds rate. But market forces set equity prices, intermediate-to-long term Treasury bond yields, credit spreads, currency exchange rates, and a variety of other tradeable instruments.

Late last year, investors began to signal that the Fed’s hawkish tone on interest rates was wrong-footed. Stocks sold off by almost 20% between late September and late December, and credit spreads widened materially. By early January, bond investors were demanding .64% more yield to finance BAA-rated bonds than they had during the first week of last October. That might not sound like a lot, but this was the biggest 60 trading-day increase in investment-grade credit spreads since late 2011, and it translated into much higher costs of debt capital for domestic corporations. In effect, the markets tightened financial conditions all by themselves, and in doing so they did much of the Fed’s heavy lifting for them. While we have no special insight into the mindset of Fed Chairman Powell or his colleagues, their recent comments have downplayed the prospects for further rate hikes in 2019. We think this dynamic has contributed to the strong rebound in stock prices so far this year. More importantly, we think the Fed would be correct to keep future rate increases on hold in the coming months. After all, inflation remains subdued, the US and China remain embroiled in contentious trade negotiations, and the pace of global economic growth is slowing. In our opinion, this is not the type of environment that would indicate an aggressive or hawkish Fed policy.